When G-d your G-d shall broaden your borders, as He has promised you, and you will say, “I shall eat meat,” for your soul shall desire to eat meat, you may eat meat to your soul’s desire.

Deuteronomy 12:20-23

“Last and first You created me” (Psalms 139:5) … If man is worthy, he is told: You are first among the works of creation. If he is not worthy, he is told: The flea preceded you, the earthworm preceded you.

Midrash Rabbah, Vayikra 14:1

There are those who contest the “morality” of eating meat. What gives man the right to consume another creature’s flesh? But the same can be said of man’s consumption of vegetable life, water or oxygen. What gives man the right to devour any of G-d’s creations simply to perpetuate his own existence?

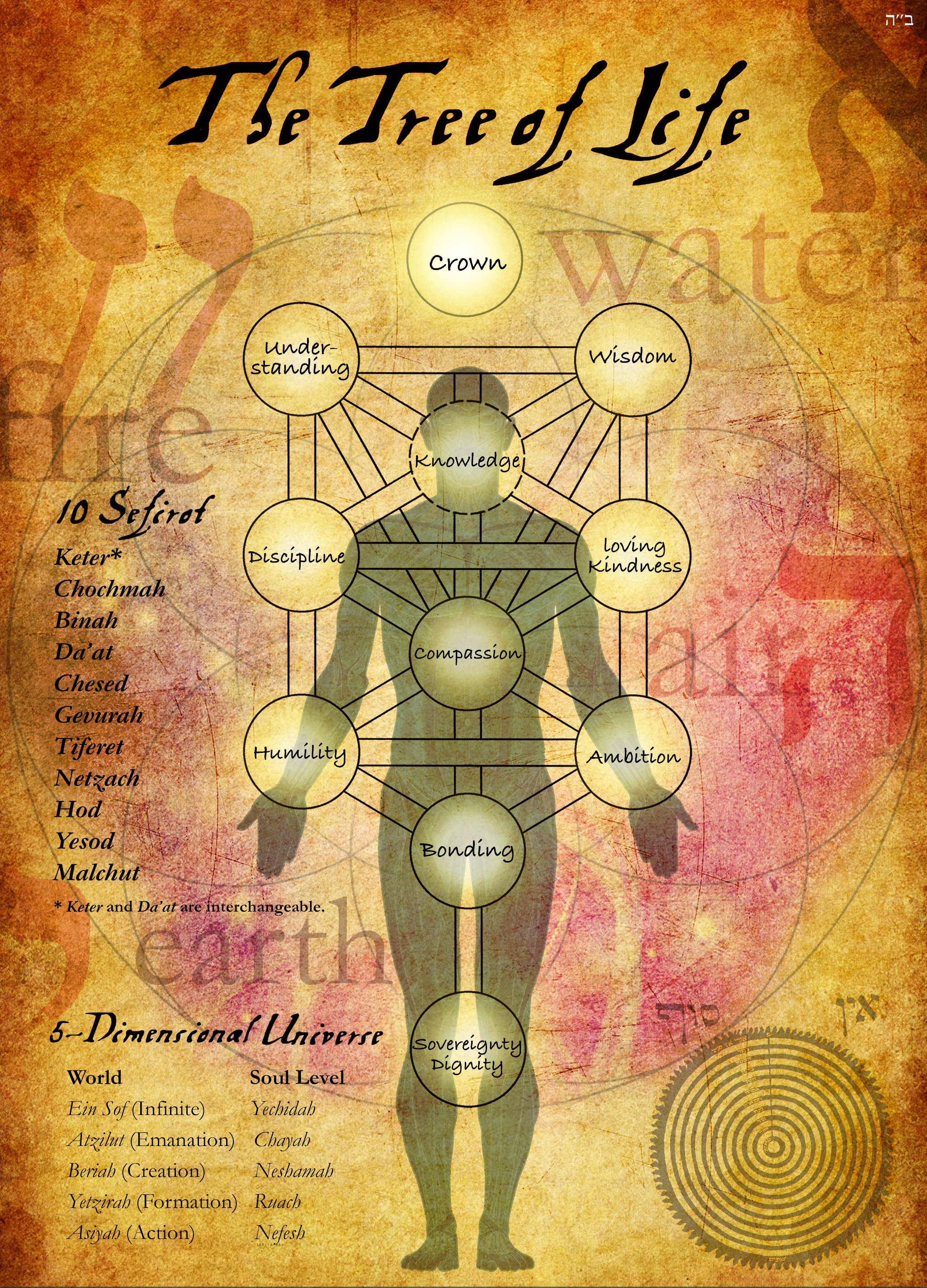

Indeed, there is no such “natural” right. When man lives only to sustain and enhance his own being, there is no justification for him to tamper with any other existence to achieve this goal. As a great chassidic master put it, “When a person walks along without a thought of G-d in his head, the very ground under his feet cries out: ‘Boor! What makes you any better than me? By what rights do you step on me?!’” 1 The fact that man is a “higher” life form scarcely justifies the destruction of dumb or inanimate creatures. Moreover, according to the teachings of kabbalah, the souls of animals, plants and inanimate objects are actually loftier than that of the human being; for in the great collapse of the primordial world of Tohu 2 the higher elements fell lowest (as the highest stones in a collapsing wall fall farthest), so that the loftier sparks of divine light came to be incarnated in the lower tiers of the physical world.

Man does have the right to consume other creatures only because—and when—he serves as the agent of their elevation. The spiritual essence of a stone, plant or animal might be loftier than that of a man, but it is a static “spark,” bereft of the capacity to advance creation’s quest to unite with its Creator. The cruelty of the cat or the industry of the ant is not a moral failing or achievement, nor is the hardness of the rock or the sweetness of the apple. The mineral, vegetable and animal cannot do good or evil—they can only follow the dictates of their inborn nature. Only man has been granted freedom of choice and the ability to be better (or worse, G-d forbid) than his natural state. When a person drinks a glass of water, eats an apple, or slaughters an ox and consumes its flesh, these are converted into the stuff of the human body and the energy that drives it. When this person performs a G-dly deed—a deed that transcends his natural self and brings him closer to G-d—he “elevates” the elements he has incorporated into himself, reuniting the sparks of G-dliness they embody with their source. (Also elevated are the creations that enabled the G-dly deed—the soil that nourished the apple, the grass that fed the cow, the horse that hauled the water to town, and so on).

Therein lies the deeper significance of the above-quoted verse, “and you will say, ‘I shall eat meat,’ for your soul shall desire to eat meat.” You might express a desire for meat and be aware only of your body’s craving for the physical satisfaction it brings; in truth, however, this is the result of your soul’s desire to eat meat—your soul’s quest for the “sparks of G-dliness” it has been sent to earth to redeem.

Desire

There is, however, an important difference between the consumption of meat and that of other foods. The difference involves “desire” and the role it plays in the elevation of creation.

The human being cannot live without the vegetable and mineral components of his diet. Thus, he is compelled to eat them by the most basic of his physical drives—the preservation of his existence. Meat, however, is not a necessity but a luxury; the desire for meat is not a desire motivated by need, but desire in its purest sense—the desire to experience pleasure.

In other words, animals are elevated—their flesh integrated into the human body and their souls made partner in a G-dly deed—only because G-d has instilled the desire for pleasure in human nature.

This means that the elevation of meat requires a greater spiritual sensitivity on the part of its consumer than that of other foods. When a person eats a piece of bread and then studies Torah, prays or gives charity, the bread has directly contributed to these deeds. In order to perform these deeds, the soul of man must be fused with a physical body, and the piece of bread was indispensable to this fusion. Man eats bread in order to live; if he lives to fulfill his Creator’s will, the connection is complete. But man eats meat not to live, but to savor its taste; thus, it is not enough that a person lives in order to serve his Creator for the meat he eats to be elevated. Rather, he must be a person for whom the very experience of physical pleasure is a G-dly endeavor, something devoted solely toward a G-dly end; a person for whom the physical satisfaction generated by a tasty meal translates into a deeper understanding of Torah, a greater fervor in prayer, and a kinder smile to accompany the coin pressed into the palm of a beggar. 3