A few weeks ago observant Jews put away their Seder plates for another year and began the seven-week waiting period between Passover and Shavuot, the holiday celebrating the giving of the Torah on Mount Sinai. It is not a well-known part of the religious calendar to those who are less observant, but it is filled with profound meanings that deserve to be better understood.

The space between the two holidays is called the Omer, and it is commemorated by the “sefirat ha’Omer,” or the counting of the Omer. The Omer was a measure of about two quarts of barley that ancient Jews brought to the Temple in Jerusalem as an offering on the second day of Passover. In Leviticus, Jews are commanded: “You shall count . . . from the day that you brought the Omer as a wave offering” (one placed in a priest’s hand and waved before God).

Even after the destruction of the Temple, the practice of counting the Omer continued — right down to the present day. On each of the 49 nights, religious Jews recite blessings and take note of the number of days before Shavuot. “The whole idea of counting the Omer is to recognize that the freedom of Passover only has meaning if one also couples it with the commitment of Shavuot,” explains Rabbi Haskel Lookstein of New York’s Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun. “One recognizes that liberty is just a step in the direction of the responsibility and commitment that are reflected in the festival of Shavuot, where the Jewish people received the Torah.”

It has also come to be a period of intense spiritual reflection. “During the 49 nights, there is a deep anxiety, anticipation and excitement as we move from a place of freedom to freedom with purpose,” Rabbi Sharon Brous of Los Angeles’s IKAR congregation said.

Eitan Fishbane, assistant professor at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, explains that the period of the Omer has long been understood to be a time of inner preparation. Mr. Fishbane, author of the book “As Light Before Dawn: The Inner World of a Medieval Kabbalist,” said that the emphasis on introspection during the Omer began with Jewish mystics in the 16th century. These Kabbalists, as they’re called, believed that religious life should be a process of “opening up consciousness and perception to see the divine presence that runs through all things.”

Later mystics, according to Mr. Fishbane, came to see the Omer as a more powerful version of the experience that Jews are supposed to undergo each week. The six weekdays represent ordinary time and ordinary consciousness, and Shabbat represents a time of transformation into “purity and heightened holiness and spiritual consciousness,” says Mr. Fishbane. “The 49 days of the Omer, the seven times seven, is an intensified process.”

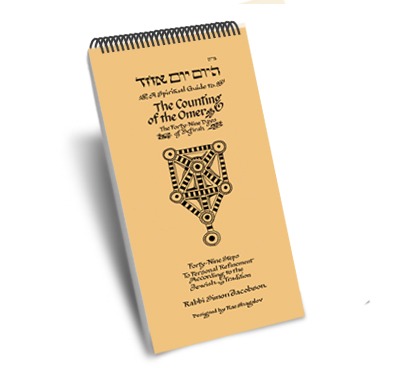

Today, Jewish congregations offer guides for counting the Omer, including thoughts for each of the 49 days. Rabbi Simon Jacobson of the Meaningful Life Center (a project housed in the Community Synagogue in New York) has taken the idea of incremental personal refinement during the Omer to its logical electronic conclusion. His center sends out daily Omer reminders by email to subscribers.

A recent email was devoted to the concept of “Hod of Tiferet,” or humility in compassion. It read in part: “If compassion is not to be condescending, it must include humility. Hod is recognizing that my ability to be compassionate and giving does not make me better than the recipient; it is the acknowledgment and appreciation that by creating one who needs compassion G-d gave me the gift of being able to bestow compassion. . . . Exercise for the day: Express compassion in an anonymous fashion, not taking any personal credit.”

While the use of email and the “exercise for the day” may sound a bit flakey, Rabbi Jacobson is quick to note that his emails are based on compilations of the teachings of medieval mystics. They are not in any way “a New Age version of Judaism,” he says, but simply more user-friendly versions of a centuries-old tradition.