Does serving G-d mean that you have to sacrifice your life for G-d? Is it conforming to be someone you’re not? Obliterating your personality?

If this sounds unappealing, it’s no wonder: It’s not only wrong, it’s an anathema to the very fundamentals of Judaism. In this week’s Torah portion, Vayikra, we learn the quintessential approach to how each and every one of us can and should serve G-d. But rather than presenting a serene picture of spiritual reverie, the book of Vayikra (Leviticus) reflects a subject that is more likely to evoke confusion, even revulsion for some, than sublimity.

In this book, we enter the bloody world of the great altar in the Holy Temple where the Jewish people brought animal sacrifices to Jerusalem to atone for their sins. What possible connection could this slaughter of ox and sheep have to do with establishing a fulfilling relationship with G-d?

The Ramban, one of the classicial commentators on the Torah, tells us that when a person had to bring a korban (animal sacrifice) to be offered in the Beis HaMikdash:

“A person had to envision that what was happening to the animal should have been happening to him or her.”

Since it is we who need to be cleansed of our wrongdoings—a cleansing of our blood, our flesh, and our fat—G-d in His great mercy gave us an alternative: we could replace ourselves with an animal, an animal that would endure this process in our stead.

But the Torah is not a lesson in ancient history; its every word is eternal and relevant to each one of us in every day and age. In a Temple-less world, we need to look a little deeper into Torah to discover the relationship of these sacrifices to our contemporary lives.

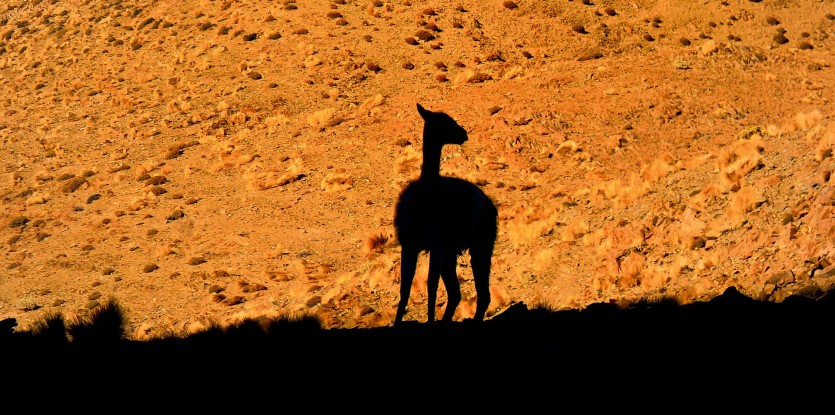

There are two polar forces within each of us: a force that desires material pleasures and a force that yearns for spirituality and G-dliness. Simply put, our search for purpose, for meaning, for serving G-d are at constant odds with “the animal” in us: the part of us that would rather indulge our selfish passions than contribute our time and resources to a higher cause. The centrality of the animal offerings in the Temple reflects the essence of our divine purpose: To submit the animal within us to G-d.

Now, when we read how a person brought a sacrifice upon the altar: “Adam ki yakriv mikem,” we find a curious twist of words. Instead of saying, “When one of you will bring an offering,” the literal translation is:

“When a person will bring an offering of you.”

The “of you” tells us that by bringing an animal to be sacrificed on the altar, we are actually bringing to the altar the animal in us.

Offering yourself, the animal in you, to G-d is the cornerstone of all Judaism, but how is this accomplished? Do you crush the animal passion and pleasure in you and live a somber life of deprivation and misery? The answer lies in the derivation of the word korban. While korban is often translated as “sacrifice,” the actual translation of the word comes from the root word kiruv, meaning “to draw close.”

We make ourselves a korban by “bringing close” the pure essence of the animal in us to G-d. We don’t annihilate it, we use it to help us approach divinity, to get closer to the quintessential purpose for which we were created. An animal cannot behave in any way other than how G-d created it. Bulls are aggressive, sheep are self-indulgent, and goats are stubborn. But the animal in us has a choice. We can be an obnoxious “bully,” or we can channel our passions toward an assertive love for G-d. We can indulge in our sheeplike lust for pleasure, or we can get pleasure in helping others and living a meaningful life.

At the heart of every force in our lives, even the ones that manifest negative expression, lies a kernel that can be directed to a constructive and G-dly cause. What we do “sacrifice” is the object of our desires, the immature or narrow attitudes we assume, our ignorance and our blind spots — so that our essential natures can emerge.

Should we “give up” our lives for G-d? Certainly not! That’s sacrifice. We shouldn’t give up our G-d-given talents and behaviors; we should bring them closer to their purer state. When you become a korban, you have the opportunity to transform every aspect of yourself, to become the greatest person you can be; a person who no longer walks among the beasts, but hand and hand with G-d.

What is the spiritual significance of the Minchah Offerings?

How could the Kohanim use crumbled bread?

Why did they use barley instead of wheat in two of the Minchah Offerings? What was the significance of the added Levona and of the types of breads they used? Thank you.