Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak of Lubavitch (1880-1950) told:

“It was summer of 1896, and father and myself were strolling in the fields of Balivka, a hamlet near Lubavitch. The grain was near to ripening, and the wheat and grass swayed gently in the breeze.

“Said father to me: ‘See G-dliness! Every movement of each stalk and grass was included in G-d’s Primordial Thought of Creation, in G-d’s all-embracing vision of history, and is guided by Divine providence toward a G-dly purpose.’

“Walking, we entered the forest. Engrossed in what I have heard, excited by the gentleness and seriousness of father’s words, I absentmindedly tore a leaf off a passing tree. Holding it a while in my hands, I continued my thoughtful pacing, occasionally tearing small pieces of leaf and casting them to the winds.

“ ‘The Holy Ari,”[1] said father to me, ‘says that not only is every leaf on a tree a creation invested with Divine life, created to specific purpose within G-d’s intent in creation, but also that within each and every leaf there is a spark of a soul that has descended to earth to find its correction and fulfillment.

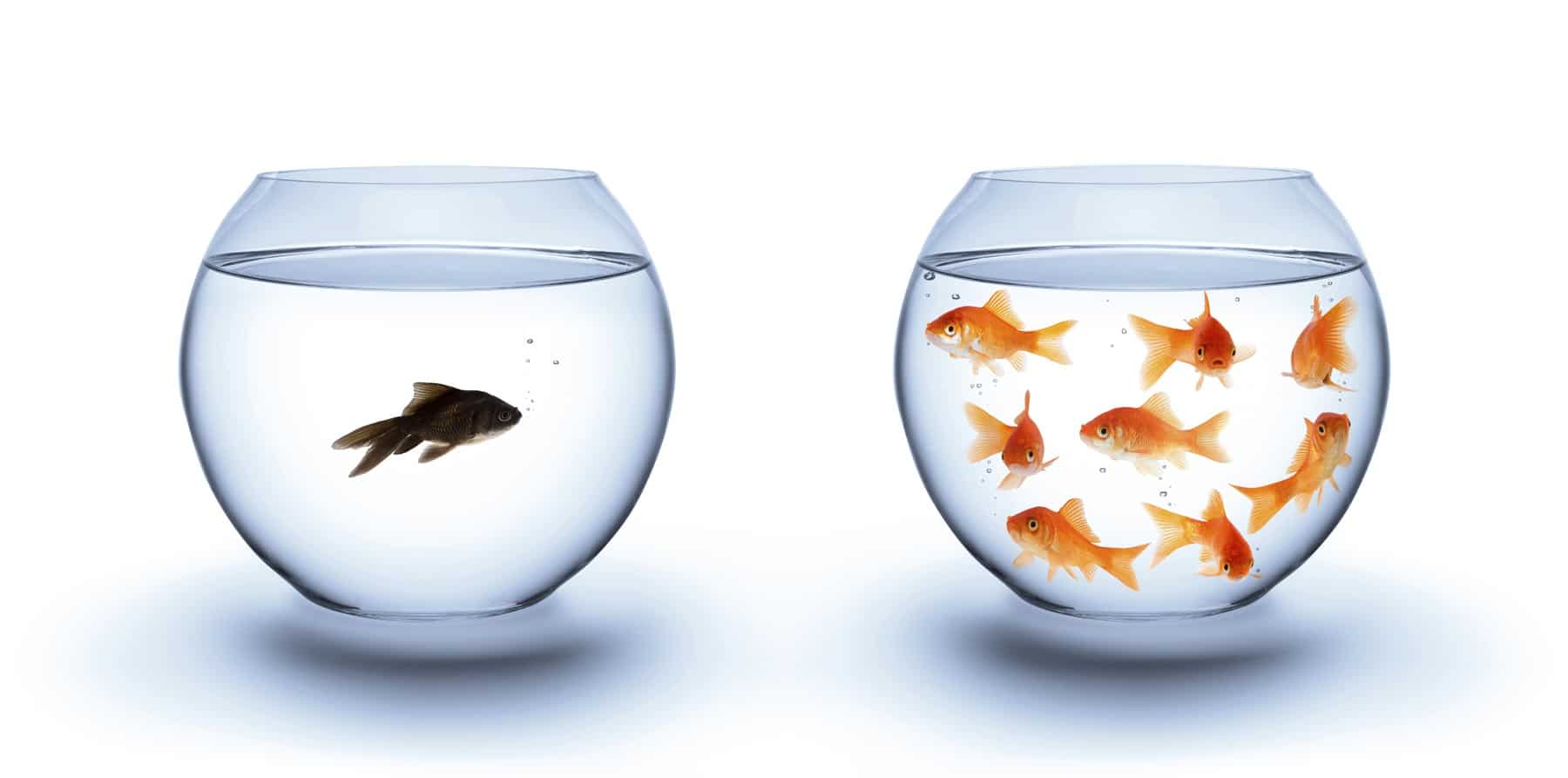

“ ‘The Talmud,’ father continued, ‘rules that “a man is always responsible for his actions, whether awake or asleep.”[2] The difference between wakefulness and sleep is in the inner faculties of man, his intellect and emotions. The external faculties[3] function equally well in sleep, only the inner faculties are confused. So dreams present us with contradictory truths. A waking man sees the real world, a sleeping man does not. This is the deeper significance of wakefulness and sleep: when one is awake one sees Divinity; when asleep, one does not.

“ ‘Nevertheless, our sages maintain that man is always responsible for his actions, whether awake or asleep. Only this moment we have spoken of Divine providence, and, unthinkingly, you tore off a leaf, played with it in your hands, twisting, squashing and tearing it to pieces, throwing it in all directions.

“ ‘How can one be so callous toward a creation of G-d? This leaf was created by the Almighty towards a specific purpose and is imbued with a Divine life force. It has a body and it has its life. In what way is the “I” of this leaf inferior to yours?’”

————

[1] Kabbalist Rabbi Isaac Luria, 1534-1572.

[2] Talmud, Bava Kama 3b

[3] I.e. cardiac and respiratory functions, digestion, cell replenishment, etc.

Leaves on trees are alive, thus tearing a leaf from its life source and twisting and shredding it and throwing it away, or stomping on it, or burning it, etc., is a murder, of sorts. Even so, the leaf does not have a soul that goes to God someday, as we do. Leaves should fall from trees only when the tree decides it it time.