The Communication Revolution

Why is it that in our age of state-of-the-art communications – smartphones and social media, e-mails and texting – we have hardly made any progress in personal communications? On an intrapersonal or interpersonal level, in families and communities, from cultures to nations, strife and discord dominate our lives and our world. With all our connections, we have never been so disconnected.

An underlying theme in the Exodus narrative – related in these weekly Torah portions – is the power of speech. Moses, the “man of no words,” is chosen by G-d to be His communicator to Pharaoh, and then later the conveyor of Torah to the Jewish people. “And G-d spoke to Moses, speak to the people…” is a phrase used hundreds of times throughout the Torah. Indeed, an entire book of Torah (the fifth book) is called “Words” – “These are the words that Moses spoke” – the words of the “man of no words”…

Pharaoh in Hebrew consists of the two words “peh rah,” evil mouth. By contrast, Passover, Pesach, is comprised of the two words “peh soch,” speaking mouth. Indeed, the Pesach Haggadah recreates the Exodus in the form of a relating a story. “Haggadah” means just that: Telling the story, from the verse “v’higadito l’vincho,” and you shall relate to your children. The Passover Seder is meant to serve as the ideal model of dialogue and communication.

We thus bring you a relevant correspondence with Rabbi Jacobson about the nature of communication that opportunely took place this week.

Dear Rabbi Jacobson,

In your exceptional article (Your Life: The Ultimate Journey) I was taken by your use of a powerful analogy (of the roadmap and tools one acquires to survive on the dark lonely island), which intrigued me and pulled me further in, until I realized – too late for me to escape – that you were talking about God, Torah and mitzvoth.

I was wondering about your style, which one encounters in many of your classes and writings. I am a marketing and communications consultant and am fascinated by the way you convey ideas, that on their own could appear alien to some of us, and yet you turn them into profound insights into the human condition and highly attractive and relevant sources of inspiration.

Michael

Dear Michael,

Let me share with you an experience. When I first began teaching my weekly class, the core group attending consisted of people from the arts and entertainment industry. They were spiritual seekers, yet many of them did not identify with any religious affiliation. In fact, quite a few – reflecting a proportionate cross-section of society – were actually turned off by established institutions of faith.

Recognizing this fact I felt a keen disadvantage trying to communicate to this group. I remember thinking: Here I am sitting with a bear and yarmulke – hardly projecting a neutral image. Before even before uttering a word some of the audience will inevitably be stereotyping me. Not with any malicious intentions, but simply based on their experience. I may be reminding some of an overbearing pious grandfather that may have shlepped him to synagogue against his own will. Or an irrelevant Hebrew school teacher that taught him hollow Bar-Mitzvah lessons. Or an angry and abusive religious authority, lashing out with guilt-ridden fire and brimstone. Or a religious fanatic, judgmental and condescending, mindlessly trying to impose dogma upon him and his friends.

Given, I may also be evoking some fond memories of the “old home.” But I was intensely aware of not being in control of how they would react to my image.

So, I tried an experiment. Instead of using any conventional words associated with religion or faith, in place of overtly Jewish and Hebrew words, I created a “new” vocabulary. Instead of the word G-d in my discussion, I used the expression “Higher Reality,” “the Essence.” For more new-age audiences – I added “non-existential states of undefined layers of energy.” I substituted “roadmap” (or “blueprint”) for the word Torah, “connections” for Mitzvot and “destination” for the Final Redemption.

An interesting discussion ensued, with the heated participation of the entire group, about a journey toward the Essence of all existence, following a blueprint and connections, all reaching a destination. We all, everyone at the class, felt the common human denominator of how we all struggle in the material world to discover transcendence in our search to connect to something higher.

After a few weeks of these classes, all masked in the language of kindred spirits, someone approached me and asked: “Are you talking about G-d”? I replied: “Yes. But shhh; don’t spoil it for the others.”

The experiment worked beyond my expectations. By stripping the conversation of “loaded” words, words that carry different meanings for different people, religious references that are fraught with stereotypes and misconceptions, we were able to create a meaningful dialogue. By using non-threatening, neutral, expressions, ones that evoke our commonality instead of our differences, we – people of such different and even dichotomous backgrounds – were able to communicate and bond with one another. We were – and until this very day – all enriched in the process.

Take the word “G-d.” Just my spelling is different than most people’s who use an “o” instead of a hyphen. Are there two people on this planet that can agree as to the definition of the word “G-d”? Try this test: Ask people you know to define G-d. Beyond the prerequisite, text-book, response – the Creator, the First Cause, a Supreme Being – no two people will define G-d the same way. For many, the concept of G-d is defined by nursery school images of a “man with a white long beard in heaven who strikes us with lightning when we misbehave.” This three-letter word is fraught with perhaps more stereotypes than any other word in the dictionary. Everyone has an opinion about G-d. Some are radical believers who die and kill others in the name of their so-called God. Others are agnostics or atheists, some radical who kill in the name of no God. No one is neutral about G-d. Because G-d has far-reaching implications, invoking personal responsibility, addressing the issues of good and evil, morality, government and education. Virtually every aspect of life is affected by our acceptance or rejection of G-d, and our definition of the word.

No wonder Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev said to his self-proclaimed atheist neighbor: “The G-d you don’t believe, I too don’t believe in.”

We conventionally like to think of words as bridges, connecting different, and even conflicting, people. Misunderstandings, often deep ones, can creep in when we remain silent and do not speak with one another. Words, then, are the way to bridge different interests.

In truth, however, words can also be forces that divide us. Use the wrong word and you can close down the person you are attempting to open up. Certain words may seem innocuous enough to us. But those same words can cause another to go ballistic.

You see, words are loaded. In childhood we may have heard a certain expressions used in derogatory fashion. Your mother may have exclaimed a particular phrase – or snickered an insulting nickname of yours – every time she was displeased with you. Those phrases then become etched in your psyche, and whenever they are used you recoil.

Words, which inherently begin as neutral and objective, take on subjective shape as they become associated with particular experiences – some pleasant and some unpleasant.

The secret of communication, thus, is about sensitivity: not only to know what words to use, but also – and perhaps even more importantly – to know what words not to use. An excellent teacher will convey ideas that resonate and engender trust. And trust is not only saying the right things, but also avoiding saying the wrong things.

Real communication is a relationship: A relationship between two people – not one dominant over the other, but a true partnership, with each one sensitive to the other, and exerting effort to ensure that the words used between them are not limited to the terms of the speaker but are measured on the terms of the listener. In effect, one can say that true speaking is listening: Applying yourself, paying attention and absorbing the needs of the one you want to reach, and then speaking in kind.

In effect, one can say that true speaking is listening: Applying yourself, paying attention and absorbing the needs of the one you want to reach, and then speaking in kind.

Moses, the communicator of G-d’s word in the Torah, was the ultimate communicator. As a man of G-d his utter humility allowed him to speak Divine words that resonated in all those that heard him speak. Moses, man of no words, had a relationship with G-d, in which they both listened and spoke to each other. This communication/relationship would take place primarily in “ohel moed,” which means the “meeting tent,” where G-d would and Moses would commune.

The Torah is all about developing a relationship between man and the Divine. “Built Me a Temple and I will rest among you.” All the references to speaking in the Torah are teaching us the method how to communicate – how to listen and how to speak.

Unfortunately, over the passing generations the Divine truths were “lost in translation.” Men imposed there own meanings, with their own words, on the inner truths of reality.

Our challenge today is to revisit the original words in their pristine meaning, before they were hijacked. We must learn to free our language from the man-made word-filled traps that lock away true ideas. This effort requires a Moses-like humility and sensitivity, to be focused not on what YOU, the communicator, want to say and on your choice of words. The focus must be on the listener, and gently finding the right resonating words (while avoiding the stereotype-evoking ones) that will convey the essence of truth.

Be careful with your language. Words can be flowers, but they also can be swords.

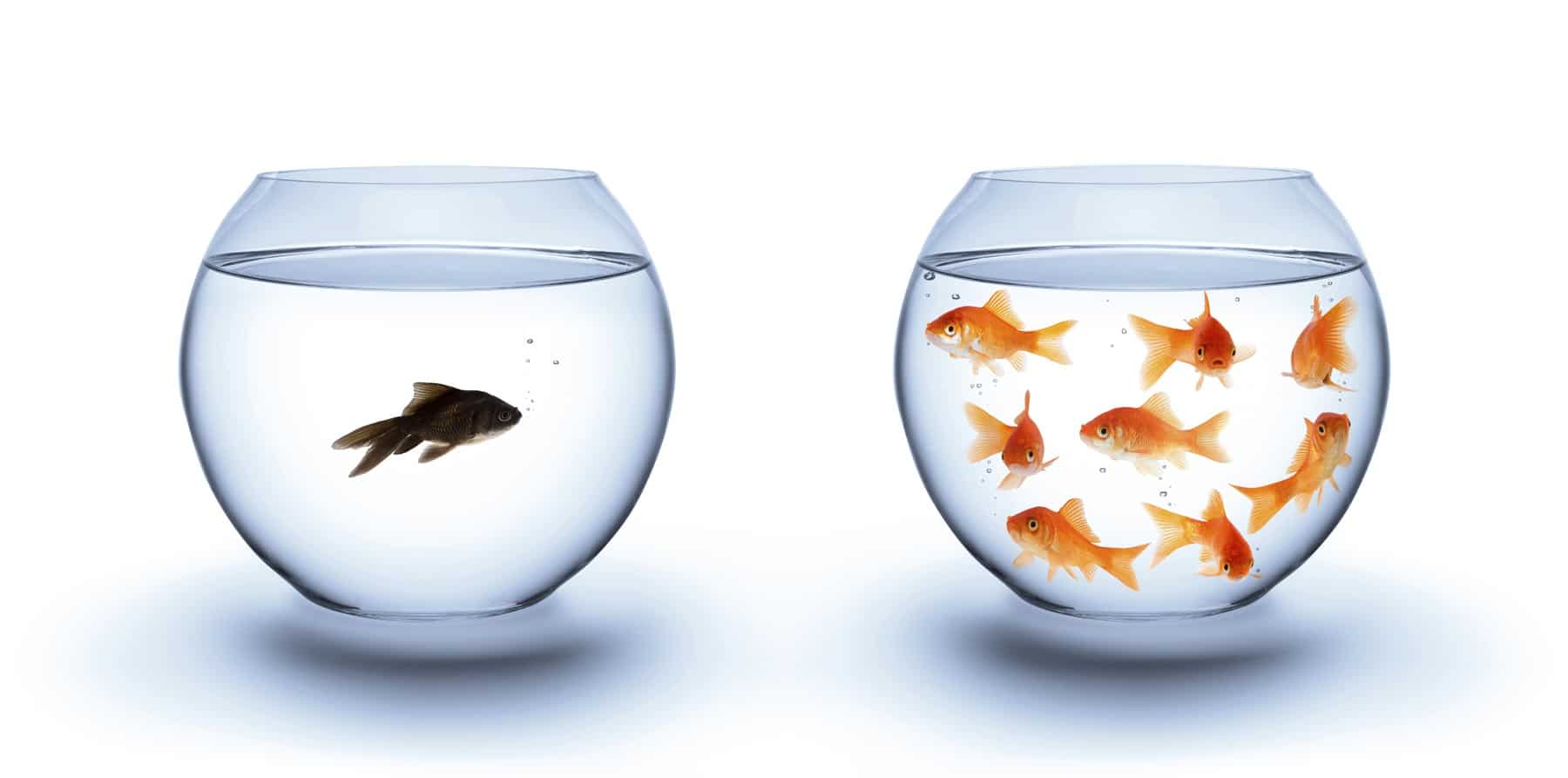

Let us declare war against stereotyping; something we all do. Stereotyping is as natural as it is shallow. At every turn in our lives we are faced with the option: To stereotype or not to stereotype. Instead of lazily fitting someone into a pre-defined, and inaccurate, mold, let us look at another as we want them to look at us: As a unique individual, not a clone nor a caricature of our imagination or an image etched on history’s canvas.

All the gadgets in the world cannot teach you sensitivity and, its direct product: true communication and a true relationship.

When we learn this secret we will have ushered in the true communication revolution.

Dear Rabbi,

Thank you for (once again) a beautiful, profound teaching. May HaShem continue to lead and direct you as you convey His heart and words to us!! May He bless you in every way and embrace you with His sweet shalom.

I really enjoyed this article. It was of great importance to us all. Communication is the key to understanding however unfortunately speakers are often too concerned with their own words and ideas. Focusing on the listener- that is indeed important to keep in mind oneveryday basis as well as special occassions. Thanks, keep on with your great work.

Rabbi: I really appreciate your clear presentation. As Michael pointed out, I got drawn into your essay and find it resonating. All of us are in search for a place where G-d, Hashem resides and comforts us, heals us and nourishes us. But then, I realized that if human kind is created in the image of G-d, then we, yes, we need to find that nourishing and loving being inside of us and allow that force to emerge and be our protector. Thanks.

I met a lovely Israeli woman in my Zumba class; she quickly assured me that she was a secular Israeli and,as such, does not believe in G-d. And I said, OK. After some chat, I asked her what she thought formed all of the magnificent world AROUND US AND SHE QUICKLY RESPONDED, A GREAT FORCE. AND I REPLIED, OH, SO COULD YOU CALL THAT FORCE G-D? SHE THOUGHT FOR A SECOND AND ENTHUSIASTICALLY REPLIED, YES, I COULD DO THAT. THE NEXT CLASS SHE APPROACHED ME AND SAID, YOU KNOW, I do BELIEVE IN G-D. SHE DOES. SINCE THEN, WE TALK ABOUT MANY THINGS. SHE IS A LOVELY BELIEVING PERSON. WORDS ARE TANTAMOUNT TO BELIEF AND HASHEM AND RENDER US WHAT WE ARE —VERY SPECIAL CREATUES OF G-D, WHO ARE HERE TO DO AND COMMUNICATE.

Thanks for helping me to see an amazing thing: Parshat Bo is my son’s parsha. When He had his barmitzva, the whole shule was crying as he is on the autism spectrum and he couldn’t talk for many years. This was a wonderful Ness and achievement in itself.

You reminded me today of the connection with Moshe Rabbenu, who was a man who had difficulty speaking.I hadn’t noticed this connection before.Two years ago, we were in Israel and went to the tomb of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai. He went to the separate men’s section and I went to the women’s section. Afterwards, I asked him if he prayed there. “No”, he answered. “I listened”.

Does G-d give assignments to those who lack the skills to carry them out, but do not lack the ability to learn the nec skills? Seems so in Moses case. What about the readers. And you Rabbi J?

Rabbi, beautiful simplified expression of such a profound topic~ thank you!